Lyn Jones

Lyn Jones

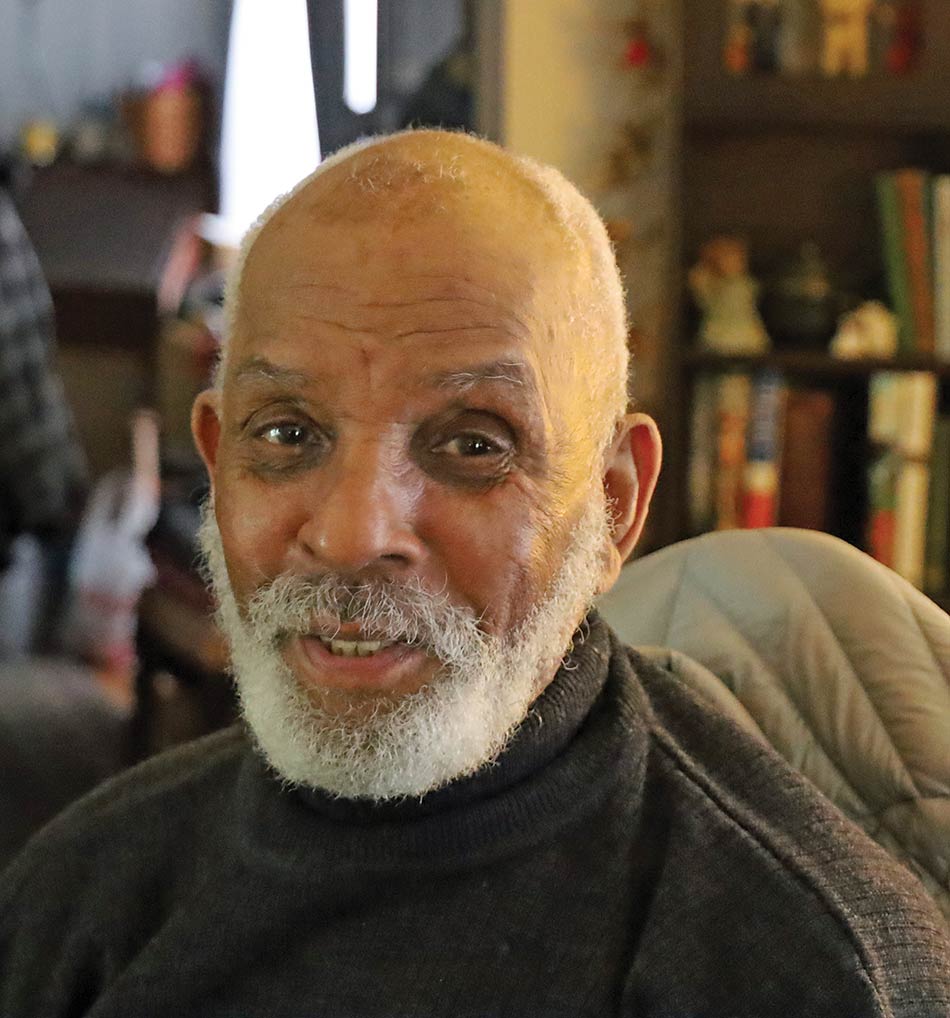

Lyn Jones of Penllyn, PA sits near a sunny window in his living room. He is surrounded by photos, news clippings, citations and other memorabilia of his decades as a horseman. There are carvings and bronze castings on the shelves next to him. On the coffee table there are books and stacks of photos. He has trained racehorses, taught riding, competed in timber racing and steeplechases and horse shows. He hunted and he galloped racehorses at area tracks. He was an outrider and a steward.

At 85, he says that life has been good. As he reflects on the years and the horses and the friends he has made, his wife Gloria sits close by, now and then supplying names he has forgotten.

Jones’ middle name might be “serendipity,” as his 76-year journey through the universe of equine pursuits was marked by chance meetings that led to opportunities that led to even more opportunities. And so it went.

He was nine years old in 1945 when his family moved from New York City to Cheyney in Chester County, PA. Consider post-war New York—a bustling city of nearly eight million people, while Pennsylvania’s entire population was fewer than 10 million people. The city kid had limited experience with vast open spaces, but he was a fearless explorer.

Chester County was and is awash in horses. “I knew nothing about horses,” he says, then jokes “I barely even knew what end they ate from!” So, one afternoon when he was riding his bike down a dirt road near his home, he saw a bunch of horses grazing in a field. Curious and surprised, he walked up to them, and was instantly smitten. “I walked around and talked to the guy who was taking care of them,” he says. The man talked to him a little about the horses, but the nine-year-old explorer with his mind already made up about these horses was impatient. “I said ‘could I ride them?’” The place where the horses lived was sort of a barn, but not the kind of barn where riders tack up their horses and take off for the fields. “He said he didn’t have any saddles,” but that was not a dealbreaker for Jones. “I just started riding there.”

No lessons, virtually no tack, no idea what the horses were capable of. “It was nice country back then,” he says of the fields and woods near Westtown. And riding seemed to come naturally to him. “I acquired some riding skills from getting thrown off,” he says. “And learning not to get thrown off.” Hacking around the area he met other riders, and became friends with Richie and Russell Jones, who would go on to start Walnut Green Bloodstock, which grew into one of the largest sales agencies outside of Kentucky.

Eventually he met a woman whose nephew, Joseph Baldwin, had shown horses. Soon he was riding at Baldwin’s barn on the weekends and after school. “He’d buy horses at the New Holland auction. The regular workers wouldn’t ride them,” he says. “So, on Saturday I would get there and clean some stalls, and then it was like Cowtown Rodeo. I really learned how to ride a horse there.” His father bought a car, and he started going to other places after school, exercising the horses and taking them over fences.

He went in the service, became a jet mechanic, came home, and got married. All the while, he thought he’d get a job as a jet mechanic. But fate intervened again. “A guy said to me—I don’t remember how I met him—he said he had a crazy horse and couldn’t do anything with him.” Jones took the horse and found a barn in Chester Heights where he could keep it. “I didn’t have a saddle, bridle, brush, hoof pick—nothing,” he says. But the people who owned the barn were a nice, elderly couple and the husband was a carpenter. He built a couple of jumps and Jones discovered that he had a quirky, spooky horse. “He turned out to be a fantastic jumper, but he was spooky. It would take an hour and a half for the blacksmith to put a shoe on him. He could snatch that hind foot out of the blacksmith’s hand so quick, kick him and then put his foot back in his hand.” The horse would spook going by a jump, but never going over. Jones won lots of big stakes classes at the Delaware County Fairgrounds on that spooky horse.

People started bringing him horses they wanted trained or sold or shown at Devon. He hunted with Radnor, Unionville, Brandywine. Eventually he started training racehorses, and galloped horses for some of the top trainers in the area. “I galloped for John Servis, Jonathan Sheppard and Marty Fallon,” he says. “I got on all the so-called bad ones, and everyone said to me ‘how come?’ They thought I was crazy. But horses are not born bad. They’re made bad by the people who don’t know how to treat them. I took my time on every horse. You can’t rush them.”

When he was in his late 50’s he took a part time job with the Wissahickon School District. He wanted to stay involved with racing and decided to go to Steward school. In the meantime, his friend Paul Jenkins, the legendary racing secretary who was then at Keystone Racetrack, said he needed outriders. “So, I didn’t know what the pay was. He says, ‘Lyn the pay is $50,000 a year.’ I said, ‘yea? I’ll be your outrider’.”

“I had a choice,” he says. “I was working part-time at the school as a janitor, part-time at the racetrack as an outrider. So, I’m waiting for one of the outriders to retire, it was the job I loved.” The supervisor at the school called him and offered him a full-time job. The same night, the racetrack called to offer him the full-time outrider job. It was a dilemma.

“Full-time at the school was $33,000 a year, but with benefits,” he says. “I think I used my head. I didn’t have any insurance per se at the racetrack. If I take the job at the school, my benefits are tremendous. Gloria was paying more than $400 a month for my insurance,” he says. The job at the school would allow him to put her on his insurance.

Shortly after taking the full-time job at the school, Jones was diagnosed with colon cancer. “I was out eight months,” he says. “I’m not sure that the track would have paid for my hospital bills and my salary.”

He kept his foot in the equestrian world, though, and worked as a Steward at the steeplechase races at Willowdale and Winterthur. “I had to stop doing it,” he says. “My downfall was my emphysema. I can’t go up those steps. Radnor’s not bad, but Winterthur? Man, that was like a ladder going up. I died. I just couldn’t go up those steps.”

Jones says he has been in and out of hospice a few times. But he’s still standing. His memories of the horses and people with whom he has crossed paths are vivid and engaging. Each photograph—even those faded by time—brings him back to a day when life was brimming with possibilities.

Among his favorite pictures are those with his family. He and Gloria still live in Penllyn Village, a place steeped in history, where they raised their three sons. She chronicled the history of the village in a 2008 book, written while she was teaching at Gwynedd Mercy College (now Gwynedd Mercy University). “I had everything planned,” he says. “But you know what they say about the best-laid plans. I’ve had a good life. Everybody’s been good to me.”