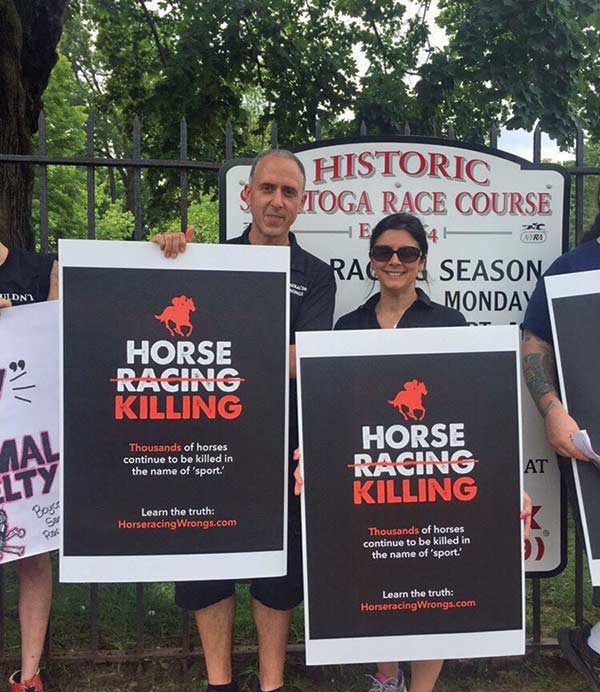

Patrick Battuello and Nicole Arciello of Horseracing Wrongs have been protesting at Saratoga Racetrack.

Patrick Battuello and Nicole Arciello of Horseracing Wrongs have been protesting at Saratoga Racetrack.

The 2017 thoroughbred racing meet at Saratoga had not even begun when a horse named Lakalas collapsed and died after breezing. It was May 28, and in retrospect, it could have been an omen presaging another tragic season at Saratoga. Since Lakalas’ death—as of August 20--15 horses have died or were euthanized after suffering catastrophic injuries. Some of the horses collapsed after training or racing. Some took a bad step and fractured bones or tore tendons.

Saratoga’s seven-week thoroughbred race meet began on July 21. With just weeks to go before the end of the season, the state’s gaming commission was scrambling to identify the root of the problems.

During the 2016 meet 16 thoroughbreds died at Saratoga. That’s just one more than the number of horses that died in the first 26 days of Saratoga’s 2017 season. The collision between the ideal of thoroughbred racing and the reality of so many deaths at one racetrack in a concentrated period of time has generated protests at the racetrack. An organization called Horseracing Wrongs monitors racetracks all over the country, and they’ve been busy handing out leaflets in Saratoga and urging people to join them in demanding an end to horseracing.

Horseracing’s Footprint in the Region is Large

It’s a tough sell in Saratoga, where the annual race meets are major tourist attractions. A 2011 economic impact study concluded that Saratoga’s race meets generate $200+ million dollars annually. That’s a combination of tourist dollars injected into the local economy, race course operations and money spent at the racetrack by visitors. Saratoga’s racetrack alone contributes more than $12 million in tax revenue to the state and the City of Saratoga Springs. And the racetrack is responsible for at least 2,000 jobs in the region.

There are deep connections to the venue among people who have grown up with Saratoga’s race meet as the centerpiece of their summers; and there is the allure of a racetrack steeped in history. It is the oldest racetrack in America and its fans think of it as racing’s grandest venue. “I’ve been going since 1982. I’ve never missed it,” Michael Shea says. He lives in Glenside, Montgomery County, PA and swears that nothing could keep him from Saratoga’s summer race meet. “If you hand me a round-trip ticket for a trip around the world in August, I wouldn’t take it,” he says. Shea has worked in economic development and he says that Saratoga Springs stands out from other cities in the region. “It has blossomed on its own. It’s a college town, but it still has an old-time feel to it.”

Shea says that the buildings at the racetrack have been patched up a lot, but “You could still go back in time. I’ve read stories about back in the 1920s when the town was really wild. It has a charm to it.”

The End of Horseracing?

But Patrick Battuello of Horseracing Wrongs is more deeply concerned about the welfare of horses; he wants people to look beyond the dollars the sport brings to the region. “I’ve had individual horsemen approach me (at the protests) and most of the time they seem genuinely interested in cleaning it up and making a difference.” But the key difference between Battuello’s goal and that of the horsemen with whom he speaks is not insignificant. “We’re out to end horseracing,” he says. “This is not a welfare-minded endeavor to us. It’s more of an animal rights campaign.”

He says that he and his group have been protesting horseracing for several years in relative anonymity. But this year has been different. “The local media was real hesitant to put out anything negative about Saratoga,” he says. “That’s what’s changed in the past two summers. Last summer the (Albany) Times Union picked up our protests. That’s what’s happening here. It’s getting a lot of press, which is good.”

Battuello says that he can sense a change in the wind, and he is hoping to capitalize on it. “We’re trying to build on the momentum of Ringling Brothers and Sea World.” He speaks deliberately, and is not blind to the ramifications of his ultimate goal. “I’m not out to demonize any individual people,” he says. “It’s why I don’t attach trainers’ or owners’ names to the database.”

He understands and appreciates the sentiments of Saratoga fans like Shea. “Saratoga is really a social attraction,” he says. The atmosphere during the race meets is unlike those at other racetracks. There is a historical setting, and there are numerous events. From artisan food vendors to tequila and Taco Thursdays the racetrack has developed programs aimed at bringing people to the venue for things other than horse races.

Shea is distressed by the deaths of horses, too. He thinks there are several reasons for Saratoga’s tragic statistics. “In the old days Saratoga didn’t have 15 breakdowns during the course of the racing season,” he says. “Up until the late 90s it was 24 days, then they extended it another week, then another week. Now it’s seven weeks.” He says he believes that trainers are often pressured to race horses that are just not ready. “Most owners want to run their horses at Saratoga. A trainer would never admit it, but they’re under pressure to run some horses that they might like to rest a bit.”

Industry in the Spotlight

There are still no definitive answers to why so many horses have suffered catastrophic breakdowns at Saratoga in 2016 and 2017, but theories abound. Theories don’t mitigate the tragic deaths of the horses, though. And the death rate in Saratoga presents a dilemma that goes to the heart of the sport’s viability and what should be an industry-wide goal of protecting the integrity of horseracing and the safety of the horses. The Horseracing Integrity Act of 2017 would create a Horseracing Anti-Doping and Medication Authority and develop rules that would apply to Thoroughbred, Quarter Horse and Standardbred racing. The Jockey Club remains enthusiastic about the bill, despite the fact that it failed to pass in the last legislative session.

At the The Jockey Club’s 65th Annual Roundtable Conference on Matters Pertaining to Horse Racing in August at Saratoga Springs, Barbara Banke of Stonestreet Farm in Lexington, KY pointed out that safety for the horses should be job one. “To win in the long term, we must demonstrate to current and future racing fans that our industry acts with integrity and elevated standards of care to protect the health of our athletes.”

It’s a lofty goal, but for Battuello and his group, that is still not enough. It’s not about winning. “We don’t believe in exploiting horses for profit in any way. It’s a very consistent, unequivocal stance we have. It’s the nature of the industry. Any time industry and animals are connected it usually ends up bad for the animals.”

NYRA Takes Additional Action to Reduce Deaths

NYRA Press release

A New York Racing Association press release issued August 21 announced that additional actions were immediately being implemented to reduce racehorse deaths and injuries. The measures went into effect at Saratoga, Finger Lakes Race Track and all NYRA tracks. They include:

Additional commission veterinarians on-hand for training: The Commission has stationed an additional regulatory veterinarian on the grounds of Saratoga Race Course during training hours to ensure that a veterinary presence exists to view horses during busy training hours and confirm that any incidents are appropriately documented and managed.

State-of-the-art monitoring of horses: Regulatory veterinarians are using reports provided by The Jockey Club's InCompass Solutions software to examine horses considered to be at an increased risk for injury. The reports will include horses stabled at Saratoga and/or Belmont Park that may be vulnerable to injury based upon extensive research findings.

Comprehensive owner, trainer and veterinary education: New York State requires Thoroughbred trainers to obtain continuing education as a requirement for licensure. These programs are regularly presented at New York State racetracks throughout the year. The Commission's rule requires that all Thoroughbred trainers, including assistant and private trainers, obtain continuing education of at least four hours each year in equine health, welfare and safety as well as small business, ethical and human resource topics.