New techniques in equine fracture repairs was the subject of a presentation at Penn Vet New Bolton Center on September 4 by Dean W. Richardson, DVM, professor and chief of large animal surgery at Penn Vet’s New Bolton Center. The lecture was part of the First Tuesday Lecture series at New Bolton Center, offering the public open lectures on equine topics, at no charge, the first Tuesday of each month.

The Tao of Fracture Repair

Dr. Richardson began his presentation by pointing out that there is a harmony to successful fracture repair, much like the yin and yang. It is a harmony of mechanics and biology. “You have to learn to think this way in orthopedics. The mechanics and the biology of the healing bone are the two elemental forces to be considered.”

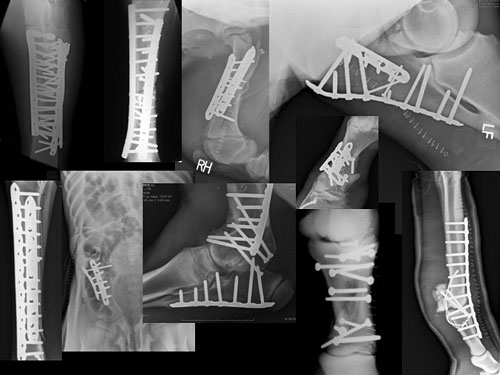

The audience was shown a series of radiographs representing severe fractures that were repaired by Dr. Richardson. The slides revealed an abundance of steel implants. “It may look like the body has been invaded by a hardware store. This is the mechanical.” What makes equine orthopedics so different from other species, and so difficult, he explained, is size. A horse puts a tremendous amount of weight on its limb and it MUST stand comfortably. If a horse does not stand comfortably after surgery, the opposite limb often breaks down. In young horses, this typically results in bad limb deformities. In older horses, the consequence can be devastating laminitis, a separation of the bone inside of the hoof away from the hoof wall. The major difference in equine orthopaedics is that consistent success demands that the horse can walk on its broken leg immediately after the surgery.

Joint Surface Fractures

In order to preserve the athletic ability of the horse, simple lag screw fixation is used to repair joint fractures. Dr. Richardson compared an outdated surgery, in which the joint is completely opened, with the examples of the latest techniques, in which the screw is placed arthroscopically, and the fracture can be observed squeezing together as the screw is tightened. Accurate position of the screw(s) and perfect re-alignment of the fracture means that future arthritis can be avoided.

Foot Bones

Certain coffin bone fractures, he explained, have proven difficult to repair because the bone sits entirely within the hoof capsule. Using an intra-operative CT (computed tomography) unit, a three-dimensional image of the fractured bone can be obtained while surgery is being performed. Having a 3-D image of the fracture and the foot allows absolutely perfect positioning of a screw even though the procedure is done through a small hole in the hoof. “We can repair many fractures with relatively simple fluoroscopy (real-time x-ray) images but the only way some particularly difficult fractures, for example the navicular bone fractures, can be accurately repaired is with intraoperative 3D images.”

Dr. Richardson explained that when they redesigned the newest surgical suite at New Bolton Center, he made it twice as big as he thought it would ever need to be. The new technologies available at New Bolton Center, however, including the fluoroscopy unit, the arthroscopy tower, the CT machine, a computer for radiographs and all of the anesthesia monitoring equipment, are filling up the suite.

A Team Sport

Every surgery involves a team, said Dr. Richardson. The nurses in the operating room are specially trained, and very experienced; there is a board-certified anesthesiologist; and the farrier plays a big role. In the coffin bone repair, for example, the holes created in the hoof wall are sealed with cement created for hip joints, impregnated with antibiotics, finished with multiple coats of a super-glue relative, topped off with a carbon fiber patch which will grow out with the hoof, and finished with a special shoe.

More Tools of the Trade

Nuclear scintigraphy allows veterinarians to identify early injuries where radiographs might not be conclusive. A slide shows a hot spot on a horse’s hock, visible with the nuclear scan. Once again, he explained, the interoperative CT is crucial for the placement of screws to repair the injury.

Dr. Richardson used the repair of a long pastern bone fracture to bring back the yin yang metaphor. With a long bone like the cannon bone, opening the leg to repair the bone might be good mechanics but it wouldn’t be good biology. More damage would have to be done in order to do some good. In order to do it better, he makes a small incision into which he slides a plate, manipulated with precision to fit appropriately along the bone between the skin and the covering of the bone (the periosteum). He then makes a series of tiny incisions to insert screws into the plate, guided by fluoroscopy so that certain highly complex fractures can be repaired without making large incisions.

Following the presentation, Dr. Richardson answered questions from the audience.

-------

Future First Tuesday lectures include: November 4, Dr. Joy Tomlinson, Headshaking Syndrome in Horses; December 4, Dr. Jon Palmer, The Critically Ill Foal; and January 8, Dr. Olivia Schroeder, Easy Keepers: Metabolic Disease in Horses.

For a complete list of scheduled lectures visit http://www.vet.upenn.edu/FirstTuesdays. Though the lectures are free, seating is limited. Please RSVP to beltb@vet.upenn.edu.